Making Matcha - from tools to types to preparation

Modern day matcha making knows no limits. From electric whisks to shaking mason jars, people make matcha in as many ways as creatively possible. However, I wanted to mention some more classical methods to matcha making.

Matcha is different from other types of green tea for the simple fact that you are consuming whole plant material, the actual leaf, rather than steeping leaves to extract flavor and chemical constituents. Simply pouring boiling hot water onto ground up tea powder would yield a clumpy, bitter beverage. Such a creation would more closely resemble the original brew created by Eisai, the Zen monk credited with the invention of matcha. To make a delicious and enticing bowl of matcha, however, requires attention to several factors, regardless of whether you prefer more classical or modern methods. You must pay heed to such details as hardware, water temperature, and of course, matcha quality. While the traditional Way of Tea ceremonies, called chanoyu (茶の湯) or chadō (茶道) in Japanese, outline numerous required steps, what I discuss below is a simplistic take on a rich and complex ritual.

Let's start with some basic equipment you will need:

- chawan, or matcha bowl

- chashaku, or wooden tea scoop/spoon

- chasen, or bamboo whisk

- metal sieve or strainer

Chawan 茶碗 or Matcha Bowl

I have written about the chawan in a previous post. Chawan can be found in a wide array of shapes, sizes, colors and materials. My preference leans toward more traditionally shaped clay bowls, but as I experiment more and more with matcha, my interests have expanded. As a chawan collector, I find myself reserving certain chawan for specific situations or occasions. I have a few I will easily use for my daily morning ritual, yet use more expensive and artistically designed chawan when serving friends or guests. I will select some other chawan when I wish to engage in a deeper meditative experiences.

The shape and size of the chawan can also dictate the type of matcha you wish to make as well - thicker or thinner matcha (read below). Regardless, each chawan has its own energy, its own particular way it rests in your hands or distinct way it feels when your lips touch the lip of the bowl. For a complete experience, selection of the chawan is part of the overall process.

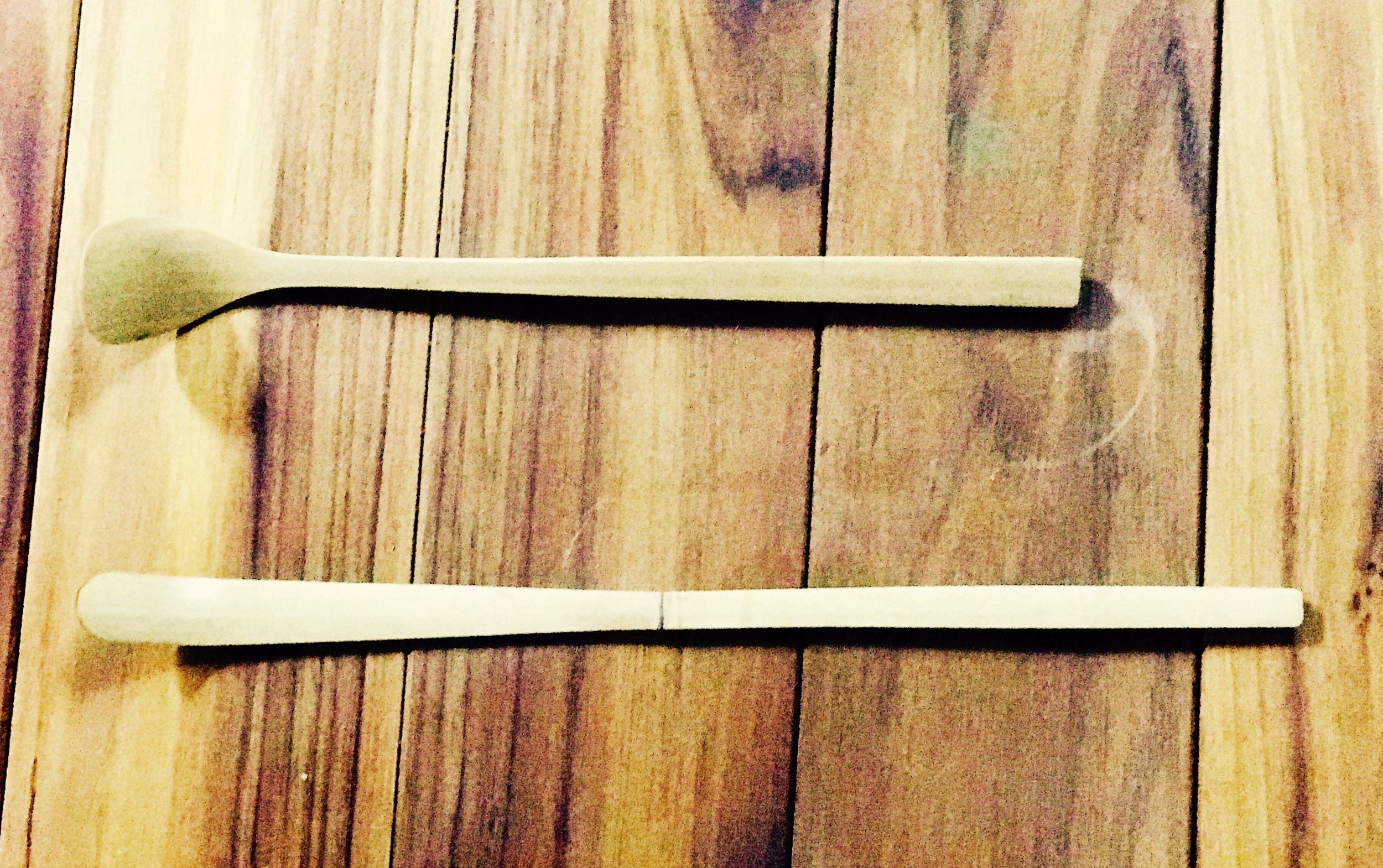

Chashaku (茶杓), or Bamboo Tea Scoop

The chashaku (cha - tea; shaku - ladle/scoop) is the wooden scoop used to measure and transfer matcha. In the traditional chado ceremony, matcha is kept in a tea caddy, called a chaki (茶器), and a large chashaku is used to fill it. This chashaku, however, remains unseen by those being served. The chashaku used to scoop the matcha during the ceremony and for our purposes here is smaller, about 18 cm in length, and has about a 48° angled curve at the flatter and slightly wider base. Depending upon the amount of matcha you can place on your chashaku, one scoop is typically about 1/3 - 1/2 tsp of a teaspoon of matcha.

Originally from China, the chashaku was made from ivory, metal or a combination of the two. Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Japanese tea masters began carving their own chashaku, usually from a single piece of bamboo. I had a few glass chashaku, which were extremely delicate, and I broke them within weeks of purchase. Needless to say, I find myself always returning to those made of bamboo.

Chasen (茶筅), or Bamboo Whisk

The whisk, or chasen (cha - tea; sen - whisk) is an essential item in the process of making matcha. Simply adding hot water to matcha powder and stirring with a wooden spoon, as was originally done, will yield an elixir that is bitter and full of clumps. Hence the creation of the chasen. Bamboo was used due to its durability (can withstand repeated, daily use), flexibility (retains shape even after all the whisking), and the fact that it does not alter the flavor profile of matcha.

Carved from a single shoot of bamboo, the typical chasen is about 10 cm in length. On the one end is the handle, which looks like the bamboo shoot, and on the other the curved prongs, ranging from 60 - 240. The process for making a chasen is elaborate, with numerous steps - from harvesting the bamboo during the proper season to boiling the wood to drying it to splitting the tines, and so forth. The curvature of the fine, thin prongs of the chasen allow for it to slide across the base of the chawan in a gentle and easy manner, without causing damage to either whisk or bowl. Due to size and shape of the prongs, the whisk helps suspend the matcha in the water, as well as helps create the creamy texture, thick brothiness, and delicious foam.

Your chasen should be given proper care and attention. Unless following the practices and dictates of tea traditions that require a brand new chasen each time a tea ceremony is performed, most of us will continue to use the same whisk for many matcha preparation. The chasen must be properly dry to prevent mold growth. Made of glazed ceramic, the matcha chasen holder, or naoshi, allows for proper air drying, separating the inner from outer tines for maximum aeration.

A fairly new trend in matcha preparation involves the electric whisk. If not used properly, as I have learned by accident, you run the risk of having more matcha on your table than in the bowl. Electric whisks are excellent at mixing the matcha with the water, and can create a creaminess to your beverage that is hard to master by hand. To prevent massive spillage, I have found it is best to use smaller chawan without such a wide base, matcha tumblers that are tall and narrow or even mixing the matcha in any taller vessel prevents massive spillage. The more you can suspend the matcha in the water, the creamier and richer the taste, and the less bitter your elixir will be.

That said, as a meditative exercise, I find myself returning to the chasen time and time again, which provides me with more practice. I do not receive the same sense of completion and fulfillment from using the electric whisk.

Now that we have our tea utensils, it is time to prepare the matcha. But first you have to decide, what type of matcha do you want - thick (濃茶 koicha) or thin (薄茶 usucha)? The difference involves the ratio of matcha and water.

Usucha 薄茶

Usucha, or thin tea, is traditionally served in the Way of Tea ceremonies. Here, more water and less matcha is used than in the preparation of koicha, Typically approximately 1.5 - 2 heaping chashaku scoops (1/2 - 1 tsp or 1 gram) of matcha per 50 - 75 ml (2 - 3 oz) of water is used per chawan. This ratio yields a lighter flavor that tends to be a bit more bitter than koicha. The matcha for preparing usucha usually comes from younger tea plants, meaning less than 30 years old. For this reason, many matcha aficionados have claimed that the matcha used in usucha is of lesser quality.

Many people use a sieve (burui) to strain the matcha into the chawan for both thin and thick preparations. But before doing so, give the chawan a rinse with warm water. Then, press, do not scrape, the powder through the sieve with the flat end of the chashaku to further separate the powder, breaking up any potential clumps and allowing for more thorough whisking. I recommend only pouring a small amount of water into the chawan at first, roughly 25 ml of water, then using the chasen to remove lumps and create a thick paste before adding the remaining water.

A note about water temperature. Do not use boiling water! This will burn your matcha and extract more of the catechins and caffeine, causing the resulting brew to be bitter and astringent, loosing its natural sweetness. Acceptable temperatures range from 70°C (158°F) to 80°C (176°F), but never above. This range allows more of the umami flavor to be detected (umami is considered one of the five basic tastes and has been described as a savory, brothy or meaty taste). And of course, you want to use clean water sources - filtered or purified water.

Now you are ready to whisk. Whisking, as I have mentioned above, is an art that takes practice. The bottom of the tines of the chasen should never touch the base of the bowl. Instead you are keeping it above, in the water, and move the chasen back and forth in a W or M motion to create a rich, fully, creamy, frothy viscosity. I have read accounts that describe the consistency of an usucha to that of an espresso, but as a life-long non-coffee drinker, this has no significance to me.

Koicha (濃茶)

A koicha is the stronger of the two preparation, and is by far my favorite. Before sitting down for meditation, I like to make a koicha. This is a matcha meditation experience of the highest caliber in my opinion. Here, more matcha and less water is used than in the preparation of usucha. The typical ratio is about 4 (or 5, if you dare) chashaku scoops (~4 grams or 1 1/2 - 2 tsp) to only 30 - 40 ml (1 - 1.5 oz) of water. You still use the chasen, but rather than whisking, you gently, attentively and mindfully knead or massage the matcha. This yields a concentrated elixir with no foam or bubbles, and with the consistency of warm honey or melted chocolate. Due to its concentrated nature, only the highest quality matcha should be used and the flavor should be full, vegetal, sweet and with minimal amounts of bitterness.

Let the entire process be a meditation for your senses. As you select your chawan, observe it fully. Hand made chawan are never completely smooth, even and symmetrical, so allow your eyes to drink in the contours and colors. Notice the lines. Run your fingers over the texture and feel its weight in your hands.

As you prepare the matcha, notice the intensity of the green. Does the color jump out at you? Is it bright, electric, and vibrant, or flat and dull? What aromas tickle your nose? Can you smell a hint of fresh cut grass or young vegetables, like baby asparagus?

Transferring the matcha into the sieve with the chashaku is an exercise in balance and patience itself. Why hold your breath and tighten your body? Breathe freely. Using gentle pressing motions, relaxing your shoulders and arms, take your time sifting the powder. You are not in a rush. Slowly pour the water into the chawan without disrupting the matcha and causing it to splash about. Whether making usucha or koicha, hold your chasen lightly in your fingers, never gripping it too tightly. Proceed to whisk or massage the matcha with love, care and intention. Rinse your chasen and return it to its stand, allowing it to rest until its next use.

Find a seat and prepare for the next stage of the experience. Bringing your chawan toward your face, observe once more with eyes and nose. Is the brew before you creamy and rich, fully of frothiness? Are the bubbles of the creama in your usucha small and tiny? Is the consistency of your koicha thick and viscous like melted chocolate? Is the smell even more pronounced now - very fresh and vegetal, not dull and dry?

And the taste... What are the first notes you detect as the matcha hits your tongue? Are you filled with a rush of sweetness (due to theanine content) or umami (due to theanine and glutamic acid)? Do you note any bitterness (due to caffeine and catechin) or astringency (due to catechin)? Excellent matcha should have a finishing or lasting note that remains on the tongue for 20 - 30 seconds, causing you to smile.

Now sit back and ride the waves of sensations that arises. Unlike the buzz from coffee or even green tea, matcha has less caffeine than those with high levels of theanine, said to increase alpha waves related to states of calm and relaxed focus and attention that can last up to six hours. However, the taste alone can increase your sense of delight.

__________

Matcha can be made in many more ways than I describe here - from lattes to lemonade. But if you are interested in exploring the more classical style of matcha, try these methods I outline. Make both an usucha and a koicha and see what your prefer. Using the same matcha, notice if you can taste the differences between the two preparations - they should have distinct flavor variations.

What are your favorite ways of making matcha? I would love to hear about them!

Chawan 茶碗 - The Matcha Bowl

I love matcha bowls. Each and every one tends to be an exquisite work of art - the textures, the colors, the designs. From sleek and simple to elaborately hand painted, the matcha experience becomes elevated as all your senses are awakened by meditating on the vessel from which you are drinking.

Matcha bowls, or chawan (茶碗) have evolved over the centuries. The word chawan refers to any tea bowl, or vessel from which tea is consumed, and was not specific for matcha. Like the tea plant itself, the chawan from which the Japanese monks and warriors drank their matcha were initially imported from China to Japan for several centuries, until the end of the Kamakura period, 1185–1333 (鎌倉時代 Kamakura jidai, which ushered in the Japanese feudalism society and the shogun warrior caste system). Until 1333, the Japanese had a zen, pardon the pun, for bowls made from Chinese temples in the Tianmu Mountain region. These chawans, called Tenmoku in Japanese (Jian in Chinese), were made in a variety of shapes, colors, sizes and materials. As the popularity and acceptance for drinking tea grew throughout Japanese culture, artisans in the Seto region of Japan began experimenting with making their own chawans, which unlike the Chinese style, had a distinct tapered shape.

The chawan bowls changed a bit during from 1336 to 1573 during the Muromachi period (室町時代 Muromachi jidai), as rice bowls, called Ido chawan, from Korea became the fashion. The Japanese called the Korean produced bowls koraimono. A bit later, during the Edo Period (between 1603 to 1868 - 江戸時代 Edo jidai), Vietnamese rice bowls called Annan ware, with their characteristic blue and white design, gained some popularity as chawans. However, during the Edo period, more and more chawan bowls were being produced in Japan, and by the late 18th century, specialized Japanese artists began producing their own intricate and unique bowls, which became highly valued in Japanese society. These artisans of chawans were considered some of the most respected and esteemed in the country.

Chawan were often identified by location (country of origin), type of clay or material, or location of the oven, or kiln, in which they were heated. For example, if the bowl was made in China, the Japanese called them karamono. If from Korea, they were known as koraimono, whereas wamono referred to a chawan made in Japan.

Today chawans come in all shapes, sizes, colors and materials. As I prefer the thicker preparation of matcha, koicha, I have developed a new passion for tumblers and smaller matcha bowls. Clay is my material of choice. Not only do I prefer the touch and feel of it in my hands, I believe clay provides the best taste for the matcha. That doesn't mean I refrain from using my glass chawan, like my small glass bowl below from the Matchaeologist or the larger chawan from American Tearoom. With glassware, you can really see the matcha much more clearly, drinking in the vibrant color of the magical elixir and foamy creama, which also creates a wondrous overall experience as well.

In tea drinking cultures (as well as with my matcha-loving friends), specific chawans are assigned for different occasions - one chawan for daily use, another for guests, and yet another for ceremony.

What is your favorite chawan? I would love to see pictures and hear your stories - where you purchased it and what do you love most about it.

A Teapot & A Teacup

On Instagram last week, one of the people I follow, Arturo Alvarez, also known as your_pencil, was doing a Teapot Giveaway. The winner was drawn from anyone who reposted one of his photos. I have followed him for a few months now, and adore all of his creations. So in an Instagram instant, I scrolled through his photos and picked this gem to repost, and waited, knowing that the recipient would be announced after the weekend.

Monday morning I opened IG and was surprised and delighted to learn that I actually won the enchanting yixing and cup below. In the traditional gong fu tea ceremony (工夫茶), which translates to making tea with skill, pu erh or oolong tea was used, and not green tea. I have no photos of the pot with tea since I cannot decide whether or not I want to use, let alone the type of tea to choose - oolong or pu erh. Decision, decisions!

I am so impressed by the intricacies of the design. I cannot imagine how much focus and control is involved in creating these beautifully delicate and detailed vessels. Studying my new teapot reminds to appreciate all aspects of the meditation on tea, and this include the craftsmanship and artistry of the tea ware.

How much do we take for granted? How often do we feel isolated and alone? Moreover, how often do we tell ourselves we are strong and independent, without need of help, support or the influence of anyone else? If you are reading this on a phone or a computer, can you appreciate the number of people who have touched your lives in this moment? Did you build your own phone? Did you generate your own electricity to charge it? Did you even lay down the cables, cords, and wires through which your power and internet run? Do you even know how to make cables and wires? We flip a switch, press a button or turn a key, and expect magically that lights will appear or machinery will move, and we smile and think we did this ourselves. But how many people are actually involved in every aspect of our lives - from growing our food, transporting it, stocking it, selling it? When you begin to think about it, in very rare instances do we do anything without help or assistance.

Thank you, your_pencil, for reminding me to examine the details in life and appreciate our interconnectedness and interdependence.